Agriculture

- Agriculture in Global Trade

- Agriculture and the World Trade Organization

- Food, Agriculture, and International Development

- The New Agricultural Economy in Developing Countries

- The Role of Agriculture in the World Economy

Agriculture is the systematic raising of plants and animals for the purpose of producing food, feed, fiber, and other outputs. Historically, agricultural production has been linked to the use of the land and the tillage of the soil, and it is agriculture that allowed humans to initially establish permanent settlements. Such establishments were possible because agriculture provided the food necessary to meet human nutritional requirements. Because of its connection to the development of human societies, agriculture is closely associated with culture through the food that it produces and the manner in which it alters the landscape. This tie to culture gives agriculture special status in society and has led it to be treated differently from other commodities in international economic relations.

With economic development, the share of agriculture as a percentage of a country’s gross domestic product (GDP) tends to decline (Chenery and Syrquin 1975). This trend ismagnified on a global level. As countries have developed, the importance of agriculture in the global economy has declined, with agriculture in the early 21st century representing approximately 6 percent of global GDP.

This aggregate measure, however, masks the continued importance of agriculture for many countries and households, particularly in developing countries. Because of its social, cultural, and economic importance, the treatment of agriculture in global economic relations has always been controversial. In LatinAmerica, for example, approximately 20 percent of export earnings comes from agriculturalproducts; inAfrica it is 14percent.Additionally, more than 40 percent of the world’s economically active population still works in agriculture, with these workers mostly concentrated in developing countries (FAO 2005). Therefore, the operation of the global economy and its influence on the agricultural sector can influence the lives of billions of people.

Disputes over agricultural trade and domestic agricultural policies have continued to plague trade negotiations, including recentmeetings of theWorld Trade Organization (WTO). These disputes have come at a time when agricultural markets have undergone significant changes, particularly in developing countries. A clear understanding of the role of agriculture in the global economy requires consideration of the importance of agriculture in global trade, its role in multilateral trade negotiations, its particular importance to developing countries, and recent trends that have transformed agricultural markets.

Agriculture in Global Trade

The value of world agricultural trade nearly doubled between 1980 and 2000, from U.S. $243 billion to U.S. $467 billion. While average annual growth in agricultural exports was substantial during this period 4.9 percent in the 1980s and 3.4 percent in the 1990s it occurred at a time of generally increasing trade volumes and at a slower pace than growth in the manufacturing sector, particularly in the 1990s when manufacturing grew at an annual rate of 6.7 percent. This difference was even greater in developing countries, where agricultural export growth was 5.3 percent in the 1990s compared to 10.9 percent for manufacturing growth (Aksoy and Beghin 2005). Thus, while agricultural trade continues to expand and is clearly important to the world economy, there has been a general decline in its relative significance over time. For both the world in general and for developing countries in particular, the share of agriculture in global trade has declined to just around 10 percent.

Along with a decline in the relative importance of agriculture, the composition of agricultural trade has shifted. First, there has been a movement away from the export of raw materials to greater export of processed products. Final agricultural products made up a quarter ofworld exports in 1980 81, but by 2000 2001 they had increased to 38 percent. Second, the commodities being produced and exported have changed from traditional tropical products (such as coffee, cocoa, tea, nuts, spices, fibers, and sugar) and temperate products (meats, milk, grains, feed, and edible oils) to nontraditional, higher-value products (seafood, fruits, and vegetables) and other products such as tobacco and cigarettes, beverages, and other processed foods. Tropical products, in particular, have declined from22 percent of agricultural exports in 1980 81 to 12.7 percent in 2000 2001 (Aksoy and Beghin 2005). The expectation is that there will be a continued shift away from raw materials and traditional products toward these nontraditional higher valued products and processed items.

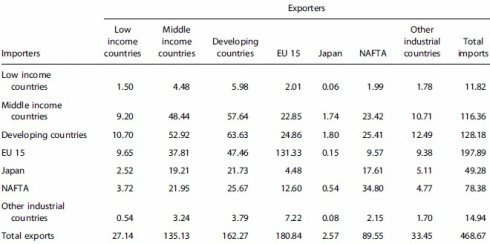

These overall trends in agricultural trade and volumes alsomask the fact thatmuch of the trade in agricultural commodities occurs within key trading blocs, particularly within the European Union (EU) and the member countries of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Table 1 shows the flows of global agricultural trade between different sets of countries in 2000 2001. Of the U.S. $181 billion in agricultural exports fromtheEUcountries, U.S. $131 billion or 73 percent went to other EU member countries. Similarly, of the U.S. $90 billion in agricultural exports from the NAFTA countries, 39 percent occurred between Canada, Mexico, and the United States.

Agricultural policies account for part of the reason why agricultural trade stays within trading blocs. Historically, developing countries have often taxed agriculture, whereas developed countries have protected agriculture from outside competition and subsidized agricultural production. During the past two decades, changes in policies inmany developing countries such as the devaluation of overvalued exchange rates, the reduction of import restrictions on manufactured goods, and the elimination of agricultural export taxes have removed the antiagricultural bias in these countries, leading to greater incentives to produce agricultural products. Developed countries, however, have continued to protect and promote agriculture through price supports and tariffs as well as direct subsidies. Within trading blocs, these protections are either not applied or are less restrictive and thus lead to greater agricultural trade within these regions.

Global agricultural trade flows, 2000 2001 (US$ billion)

Source: Aksoy and Beghin (2005) using COMTRADE data

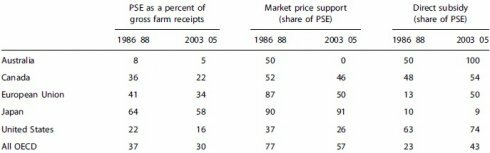

The protection and subsidies to agriculture in developed countries influence their competitiveness in domestic and foreign markets. As discussed in the next section, this has become an important point of contention in trade negotiations. To calculate the degree of agricultural protection for farmers in these countries, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation andDevelopment (OECD) has developed a method for estimating the total support to agricultural producers provided by a range of policies. The OECD’s producer support estimate (PSE) measures the monetary value of total gross transfers to agricultural producers arising from agricultural policies (OECD 2006). Compared with total gross farmreceipts, thismeasure can be used to identify the share of farmer revenue that results fromgovernment policies. Table 2 provides the estimated percent PSE in farmers’ revenue for selected OECD countries as well as for the OECD as a whole. The table also shows the share of support coming frommarket price supports, such as border tariffs, and the share coming from direct payments to farmers. The data indicate that with the exception of Australia, a significant share of farmers’ revenue in developed countries is the result of agricultural policies in those countries. Furthermore, a substantial portion of the PSE is due to market price supports such as tariff and other forms of trade protection. However, there has been a decline in the PSE for each country in the table and the OECD as a whole between 1986 88 and 2003 5, and with the exception of Japan, there has been a shift away from market price supports toward direct subsidies. These agricultural policies, however, continue to influence the trade flows of agriculture into and out of developed countries. The sheer size of the economies where these policies are in place means they have a significant impact on global agricultural trade.

Producer support in selected OECD countries

Source: OECD (2006)

Agriculture and the World Trade Organization

The protection and support of agriculture in a number of developed countries has been justified on the grounds that agriculture deserves special consideration because it is linked to national culture. This special status has been recognized by the multilateral trade negotiations that have occurred under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and later under the WTO. Under the GATT, at the initial urging of the United States, certain agricultural sectors were exempted from the general prohibition in the agreement against quantity restrictions, as were export subsidies. As the EU took shape, it developed a Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) that provided general protection and support to farmers in allmember countries and led to strong and increasing support by the EU for the special status of agriculture in multilateral trade negotiations.

The EU, the United States, and Japan remain strong supporters of the special status of agriculture. Countries that wish to export their agricultural products to these markets, however, argue that these policies are unfair since not only is access limited for certain commodities, but the subsidies provided to producers in these protected markets give them an advantage over producers in countries without such subsidies. Developing countries tend to be particularly critical of agricultural supports since they are not in a budgetary position to support agriculture and believe agriculture is one area where theymay have a comparative advantage.

When the WTO was created as part of the Marrakesh Agreement in 1994, a specific Agreement on Agriculture was designed to align agricultural trade rules with those of other products. The Agreement on Agriculture dealt with three general issues that influenced global agricultural trade: market access, domestic support, and export subsidies. For market access, the agreement required countries to convert quantity restrictions to tariffs.Once tariff equivalents of quantity restrictions were established, they were to be reduced. For domestic support, the agreement distinguished between trade distorting measures, which countries were required to reduce, and nontrade distorting measures. As part of the Agreement of Agriculture, developed countries agreed to reduce the total aggregate measure of support (AMS) by 20 percent by 2000, while developing countries agreed to reduce it by 13 percent by 2004. Nontrade distorting measures were exempt from reduction commitments. A final special category of domestic support measures was also exempt from reductions. These measures, which were used especially in the EU, covered payments under programs designed to reduce the overproduction that occurred under other traditional market support payments. For export subsidies, no new subsidies could be introduced and existing subsidies had to be reduced by 36 percent in value by 2000 for developed countries and by 24 percent by 2004 for developing countries, although special conditions applied in some cases (Ingno and Nash 2004). The changes in the rules governing agriculture are reflected in the data presented in table 2, which shows a general reduction in producer support among OECD countries and a shift from market price support to direct subsidies.

The Agreement on Agriculture has generally been viewed as a step forward for trade negotiations; although it did not bring about substantial changes in the short run, it did set up a framework that aligned agriculturewith other products. Its supporters hoped that setting up this framework would lead to further liberalization of agriculturalmarkets in future rounds of WTO negotiations, particularly in the current Doha Round of trade negotiations. In fact, the Ministerial Declaration launching the Doha Round put agriculture as the first item on the agenda, indicating its priority in the negotiations. However, the Doha Round has failed to make substantial progress and the negotiations have faltered largely because of disputes over agricultural issues. For example, prior to a WTO meeting in Cancun in 2003 a group of developing countries, referred to as the G21, stated clearly the importance of dealing with agriculture issues such as protectionism and farmer subsidies. The Cancun meeting made no progress on these agricultural issues and was generally viewed as a failure. Following aWTOGeneral Councilmeeting in July 2006 and the continued failure to make progress, the chairman of the WTO’s Trade Negotiation Committee noted that agriculture is ‘‘key to unlocking the rest of the agenda’’ and that there was ‘‘no visible evidence of flexibilities’’ that would help solve existing problems (WTO 2006). Agriculture, thus, remains the principal stumbling block to further trade liberalization.

Complicating the disputes over protection and support of agriculture are additional issues that have emerged as the Doha Round of negotiations has progressed. First are market access barriers that have been put in place because of domestic concerns about methods used for production.While this is a broader concern for trade negotiations, it is particularly important for food products where health and safety concerns are significant and where countries may legitimately claima right to protect their consumers. Although international agreements and standards exist, separating legitimate from illegitimate standards imposed by particular countries is not straightforward. The case of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) is a good example. Because of concerns over the health and environmental impacts of such products, the EU has enacted laws requiring the labeling and traceability ofGMOs.However, the United States has challenged these policies as illegitimate restrictions on trade, arguing there is no evidence to support such concerns. The dispute remains unsettled (Zarrilli 2005). A second issue is the protection of geographical indications (GIs), names or labels used to indicate the geographic origin of certain products and, by extension, to indicate that these products have certain qualities or meet certain standards of production because they are from a certain region.Many foodand beverage terms such as Parmesan and Gorgonzola cheeses, Parma ham, Chianti, and Champagne have come to be used generically although they have specific geographic origins. The EU and a number of developing countries argue that if the products are produced through a traditional, controlled manner in a specific region, their names should be protected and that existing protection is insufficient. The EU has proposed amending the current protection under the Trade- Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS) agreement in favor of a mandatory multilateral systemof registering these types of products (Evans and Blakeney 2006).

Food, Agriculture, and International Development

Of the 1.2 billion poor people in the world, 75 percent live in rural areas (IFAD 2001). Therefore, although the contribution of agriculture to global GDP continues to decline in importance, it remains a fundamental component of the livelihood strategies of these households and is critical to the advancement of the less-developed countries. Not only does agriculture provide food for the survival of the rural poor, it may be an important path out of poverty, particularly if the poor can take advantage of opportunities to produce nontraditional, highvalue crops, which tend to be labor-intensive. The manner in which the global economy operates can alter the prices farmers fetch for their products, thus offering them incentives to produce more or less depending on the direction of price effects. Trade policies in developed countries therefore have an impact not only on developing economies, but potentially on the level of rural poverty in those countries.

Other than altering the incentives for farmers in developing countries, the policies of developed countries affect developing countries’ agriculture through food aid. As a result of incentives for overproduction in their agricultural policies, many developed countries have food surpluses. A portion of these surpluses is often used as food aid to developing countries. Although this seems a reasonable response to hunger, critics of food aid have argued that the provision of food creates disincentives for local production and policy. Increasing the supply of food commodities may cause prices of food to decline, thereby leading to lower incentives for farmers, rich and poor alike, to produce.The provision of food aid may also limit investment in agriculture by developing country governments that count on a regular supply of food aid to overcome limitations in food availability. This can limit the development of the rural economy and perpetuate a state of dependency. Most of these issues can be overcome with the judicious use of food aid in emergency situations and the careful management of aid programs when implemented, but the use of surpluses for food aid has the potential to cause significant problems for developing economies (Barrett andMaxwell 2005).

Given the importance of agriculture as a productive activity in developing countries, particularly in the poorest countries, the manner in which it is treated in global economic relations, and the agricultural policies enacted by key players in developed economies, can have a profound impact on economic development.Trade controversies are then closely linked to broader global issues of poverty and equity.

The New Agricultural Economy in Developing Countries

In recent years, agricultural production in many developing countries has undergone profound changes, leading it to become increasingly oriented toward high-value global and urban product markets. These changes have mirrored many of the changes that occurred in developed countries earlier and have been driven largely by changes within developing countries. On the demand side, these include increased urbanization, the expanded entry of women into theworkforce, and the development of a middle class all of which have led to greater demand for higher-quality and processed foods (Reardon et al. 2003). On the supply side, the opening of markets to foreign direct investment (FDI) influenced not only manufacturing sectors but also the domestic food market and the role of agro-industry in thosemarkets.These domestic changes, combined with the expanded trade in processed and nontraditional products, have had a profound effect on the workings of the agricultural sector in many developing countries.

Referred to by some as the ‘‘newagricultural economy,’’ these changes have led to new organizational and institutional arrangements within the food marketing chain as evidenced by new forms of contracts as well as by the imposition of private grades and standards for food quality and safety. Where openmarketswith a variety of sellers of different food commodities used to operate, there are now frequently supermarkets.Where small-scale processors of goods for the domestic consumermarket such as potato chips used to exist, multinational corporations have taken over. Other multinationals have invested in the production of high-value crops such as fresh flowers and vegetables for immediate export to foreign markets. These supermarkets, processors, and exporters have specific requirements for the commodities they wish to purchase in terms of the quality of the goods and the timing of receipt. Products destined for the foodmarket, in particular, often must meet certain sanitary and phytosanitary standards. To ensure those requirements are met, these buyers often procure their goods through contracts with producers rather than through spot markets.

These rapid changes have brought new challenges and opportunities to farmers and policymakers in developing countries. These new markets provide significant opportunities because they tend to provide a price premium for quality and high-value products. But they alsomay be difficult to access and, in some cases, involve substantial risk. Often, new inputs and varieties are required and farmers must have sufficient information on grades and standards to be successful. Governments can play a critical role in facilitating access to information as well as providing assistance with the transition into these markets. This is particularly important for poorer farmers who often lack the resources to take advantage of new opportunities. Governments also play a critical role in verifying and certifying that sanitary and phytosanitary measures are in place. Furthermore, since such standards are often used as amechanismto limit trade, governments may be called on to ensure that limits to market access are legitimate under the WTO rules.

The Role of Agriculture in the World Economy

While agriculture continues to decline in its overall economic importance in global trade, its special status in trade negotiations and its critical role in economic development and global poverty alleviation make it a sector that will continue to play a critical role in the world economy. In the short run, agricultural issues are likely to dominate trade negotiations. In the long run, global and domestic agricultural policies will influence the ability of countries to develop, and for the poor within those countries, to exit poverty. Agriculture will continue to be part of any discussion of global economic relations. See also Agreement on Agriculture; agricultural trade negotiations; Common Agricultural Policy; distortions to agricultural incentives; primary products trade; sanitary and phytosanitary measures