Competitive advantage

- Acquiring a Competitive Advantage

- National Competitive Advantage

- The Porter Diamond

- Clustering and Sustainability

- A Multiple Diamond Approach

- Competitiveness

Acquiring a Competitive Advantage

Firms acquire a competitive advantage by creatingmore value than their competitors in the value chain.The latter is the system of activities (both primary and support activities) that the firm undertakes in the process of value creation.As goods pass through the value chain, value is created at each stage, fromupstreamsuppliers to downstream sales and marketing outlets. Equally important is the contribution made by nonproduction activities such as research and development (R&D) andmanagement services. In this process, an important decision is how to configure each of the activities within the value chain and how to coordinate these activities.Configuration refers to decisions about where to locate each particular activity and how many locations to have for each activity. Coordination relates to the decisions about how to link together the same activity performed in different locations and how to coordinate that activity with other activities in the value chain.

National Competitive Advantage

In a later work titled The Competitive Advantage of Nations, Porter introduced the notion of national competitive advantage to refer to ‘‘the decisive characteristics of a nation that allow its firms to create and sustain competitive advantage in particular fields’’ (Porter 1990, 18). Such a concept must be distinguished from the concept of comparative advantage used in classical trade theory to refer to the relative cost advantage that a nation enjoyswhen entering into trade with another country. In classical trade theory, such an advantage was measured in terms of the relative amounts of labor time that producers in different countries required to produce different goods. Later, neoclassical trade theorists explained such differences in terms of factor endowments and the different factor proportions required to produce different goods.While recognizing the usefulness of the concept of comparative advantage for explaining patterns of trade, Porter called for a ‘‘new paradigm’’ based on competitive advantage.

Porter argued that what matters when determining why a particular nation succeeds in a particular industry is the competitive environment of the nation, as this shapes the success of the firms based in that country. This is determined by a number of factors, including the following:

-

Factor conditions. These consist of human resources (quantity, quality, and skills of the workers), physical resources (abundance, quality, accessibility, and cost of land and other natural resources, including climatic conditions and location), knowledge resources (scientific, technical, and market knowledge), capital resources (amount and cost of capital to finance industry), and infrastructure (including transportation system, communications system, health care system, housing, cultural conditions, and quality of life). While neoclassical theory explained national comparative advantage in terms of factor conditions, it assumed that countries were endowed with fixed amounts of these factors. However, although some factors are given (e.g., land and natural resources), countries can add to their stock of other factors through factor creation or investment by individuals or firms.

-

Demand conditions. Three broad attributes of domestic demand matter its composition, its size and rate of growth, and the ways in which it is internationalized. With regard to the composition of domestic demand, the segment structurematters (by giving firms an advantage in segments where domestic demand is strong), as does buyer sophistication (with firms gaining an advantage in sectors where domestic buyers are among the world’s most sophisticated and demanding) and the presence of anticipatory buyer needs (domestic buyers are ahead of buyers in other countries).With regard to demand size and the pattern of growth, a large market can enhance competitiveness through economies of scale and learning effects. Also, where demand is rapidly growing, firms may invest more and adopt new technologies more quickly. Finally, it matters how domestic demand is internationalized, pulling a nation’s products or services abroad.This canhappen as sales of the product to multinational buyers increase and through domestic needs being transformed into foreign needs. The latter can happen through travel and is particularly applicable to cultural goods, such as films or television programs.

-

Related and supporting industries. This refers to the presence within a country of internationally competitive supplier industries or other related industries. Porter identified two mechanisms through which a competitive advantage in one industry could benefit other related industries. First, a supplier industry may provide a downstream industry with regular supplies of low-cost inputs and possibly privileged access to these inputs. Second, close working relationships between suppliers and an industry will result inmore sharing of information andmay result inmore rapid innovation within the entire industry.

- Firm strategy, structure, and rivalry. First, the way firms are managed in a particular country and choose to competematters a greatdeal.The country’s managerial system, the management practices and training, the way in which firms are organized and run, and the extent to which firms are globally oriented and willing to compete internationally are all part of this. Second, the goals of firms within a particular country, along with the motivation of employees and managers, may also contribute to a country’s being successful in a particular industry. Third, the more vigorously firms compete with one another in a particular industry, the more likely that a country will develop and successfully sustain a competitive advantage in that industry. Policies designed to create ‘‘national champions’’ by encouraging two or more firms to merge rarely succeed. An important aspect of domestic rivalry is also the ease with which new businesses can be set up in a country and the extent to which they are.

The Porter Diamond

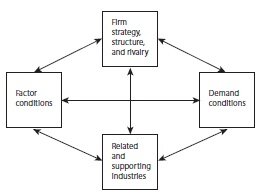

Traditionally, these factors are represented by the ‘‘diamond’’ diagram shown in figure 1. In addition to these four factors shaping the competitive environment of a country, Porter emphasized the importance of two other factors that may separately contribute to a country’s acquiring a competitive advantage or prevent its doing so. The first is the role played by chance events, such as an invention, shortages of key inputs, a sudden rise in the costs of inputs, significant shifts in exchange rates, wars, or the political decisions of government. The second is the role of government policy, which may influence firms in a particular industry either positively or negatively.The extent to which government intervention has contributed to the emergence of a national competitive advantage in particular countries is hotly debated. Advocates of government intervention point to the experiences of Japan and Korea as examples of how such intervention can work.By contrast, the same policy largely failedwhen applied byWest European governments to Europe’s electronics industry. Government intervention is viewed by Porter as working through the four main determinants of the diamond rather than constituting a fifth factor.

Porter’s diamond Figure 1

An important aspect of the phenomenon of national competitive advantage is that it is an evolving process, in which all the factors interact, with each determinant influencing the others. This process of interaction is as important as the presence or absence of each of the factors viewed separately. Thus factor conditions at any given time are determined by factor creation in the form of investment in education and infrastructure and, more important, investment in the creation and upgrading of advanced and specialized factors such as science and technology. Such investment is stimulated by a strong element of rivalry between domestic firms.Demand conditions are also affected by the existence of intense rivalry, which helps create a large domestic demand for the product through investment in marketing, aggressive pricing policies, and the introduction of more varieties of the same product. The development of related and supporting industries is affected by all of the other factors, as is the degree of domestic rivalry among firms.

Clustering and Sustainability

An especially important role in this process is played by the geographical concentration of industries in a particular region, resulting in the phenomenon of clustering. Clustering is a readily observable feature of the economies of most countries. It exists because of the relationships among the four factors in the diamond and the need for firms to be close to exploit these advantages. Within a cluster, the competitive advantage enjoyed by one industry helps create or sustain the competitive advantage enjoyed by another in a mutually reinforcing process. An example of this is where competitive supplier industries enable a country to sustain a competitive advantage in downstream industries. The same dynamic processmay equallywell happen in reverse, however.

A further aspect of Porter’s diamond model concerns the importance of sustaining a competitive advantage. It is not sufficient for firms in a country to obtain a competitive advantage in a particular industry; that advantage must be sustained by a processing of widening and upgrading. Some of the factors that give rise to a competitive advantage are also important in sustainability. These include investment in institutions that undertake research and generate new ideas, the composition of demand and the intensity of domestic rivalry, and the extent to which the different factors in the diamond interact.

A Multiple Diamond Approach

One of the major criticisms leveled at Porter’s model is that it fails to adequately address the role of multinational enterprises in the determination of national competitive advantage. In 1993, John Dunning argued that Porter was mistaken in arguing that the firmspecific advantages of multinational companies could be explained purely and simply in terms of the competitive advantages of their home countries (Dunning 1993). Multinational companies derive their advantage from the national diamond existing in a number of countries, not just the home country. If Porter’s model is to be applied to international business, Alan Rugman has argued that a ‘‘multiple diamond’’ approach is needed (see Rugman and Verbeke 2001). The weakness of the Porter model, argue Rugman and Verbeke, is that it concentrates entirely on what they call ‘‘non-location-bound’’ firm-specific advantages that are developed by firms in home countries before they engage in foreign direct investment (FDI) and which can then be transferred to other branches of the firm. This ignores, however, the advantages that multinational companies, which have already engaged in FDI, enjoy from having value-added activities in several locations and from their common governance. Some of these advantages are ‘‘location bound,’’ which means that they derive from a particular geographical area and cannot easily be transferred abroad.

The need for such amultiple diamond approach is especially relevant in the case of small countries, where firms are able to overcome the problems of a small domesticmarket by increasing their sales in the markets of other countries. Rugman and Collinson have illustrated how the Porter model could be applied to the analysis of the problem of international competitiveness with reference to firms in Canada (Rugman and Collinson 2006). Using a double diamond model, Rugman and Collinson show how Canadian firms have used exports to the United States and their rivalry with U.S. firms to develop a global competitive advantage in particular industries. In effect, the Canadian and U.S. markets served as two domestic markets through which Canadian firms could become globally competitive. Such an advantage may be acquired through developing new innovative products and services for consumers in both markets, drawing on support industries and infrastructures in both countries, and making freer and fuller use of the physical and human resources of both countries (Rugman and Collinson 2006).

Competitiveness

One of the effects of the focus on competitive advantage since the 1980s has been an increased fascination with competitiveness rankings of countries.Two examples of this are theGlobal Competitiveness Report by the World Economic Forum (WEF), and the World Competitiveness Center’s Yearbook. Such listings seek to rank countries in terms of competitiveness using a range of criteria such as economic performance, government efficiency, business efficiency, and infrastructure. The 2006 rankings of the WEF placed Switzerland, Sweden, and Finland respectively in the top three places in the world. It should be pointed out, however, that it is comparative, not competitive, advantage that determines what goods a country specializes in. This is because trade is a positive-sumgame in which all countries gain, not a zero-sumgame in which one country gains only at the expense of another.

This point is well made by Paul Krugman in a short essay first written in 1994, in which he comments on what he called the ‘‘dangerous obsession’’ with competitiveness (Krugman 1996). Using the example of Japan achieving a higher level of productivity than the United States, Krugman writes, ‘‘While competitive problems could arise in principle, as a practical, empirical matter, the major nations of the world are not to any significant degree in economic competition with each other. Of course, there is always a rivalry for status and power countries that grow faster will see their political rank rise. So it is always interesting to compare countries. But asserting that Japanese growth diminishes US status is very different from stating that it reduces the US standard of living and it is the latter that the rhetoric of competitiveness asserts’’ (Krugman 1996, 10).

Achieving a national competitive advantage is important in enabling some countries to grow faster than others. An obsession with competitiveness, however, is dangerous, as Krugman argues, because it can lead toprotectionismand trade conflict, aswell as misguided public spending designed to create and sustain a national competitive advantage over other trading partners and the promotion of national champions.

To summarize, acquiring and sustaining a competitive advantage can be seen as the primary strategic aim of firms in the modern world economy. The source of national competitive advantage is to be found in the competitive advantage obtained by the firms operating in the country, both domestically owned and foreign owned. This, in turn, is the product of a complex set of factors that interact with one another to shape the competitive environment of the country. Unlike comparative advantage, however, competitive advantage is a dynamic concept, in which national competitive advantage continuously evolves. In a world in which multinationals are dominant, the source of such advantage often results from firms operating in more than one country. Despite its usefulness in explaining why some countries develop a specialization in a particular industry or branch, an emphasis on attaining a competitive advantage can cause governments to pursue misguided policies that lead to trade conflict. It remains the case that trade is a positive-sum game in which all can benefit. See also commodity chains; comparative advantage; foreign direct investment (FDI); foreign direct investment: the OLI framework; New Economic Geography